The establishment (1716)

In 1715 a heavy storm devastated the woods in the region south of Baruth. Earlier plans to build a glassworks north of Baruth had been put on hold because of the prohibitive costs of raw materials, but thanks to the unexpected supply of windfall timber the decision was made to build the glassworks at its current location.

Count Friedrich Sigismund of Solms-Baruth summoned a master glassblower by the name of Bernsdorf from Lusatia to Baruth. A contract for the construction of the glassworks was signed on March 23 1716.

A technique for making clear and colourless glass using potash was developed around 1650. This required far greater amounts of wood than earlier methods as wood was needed not only as a source of energy but as raw material for the potash.

Bernsdorf, the master glassblower, was permitted to extract 1000 klafter – roughly 3000 cubic metres – of wood from the forest each year. Transporting the wood, equivalent to 50 lorry-loads, would have kept teams of horses and carts busy all year round.

Although the energy-intensive potash process used in the Baruth glassworks was technologically advanced and produced excellent “blue” glass, high running costs meant the business was seldom profitable. The glassworks changed hands, and production ceased for a number of years. During the Seven Years’ war (1756-1763) a new team of skilled glassworkers arrived from Glückburg.

The Golden Age (1822-1880)

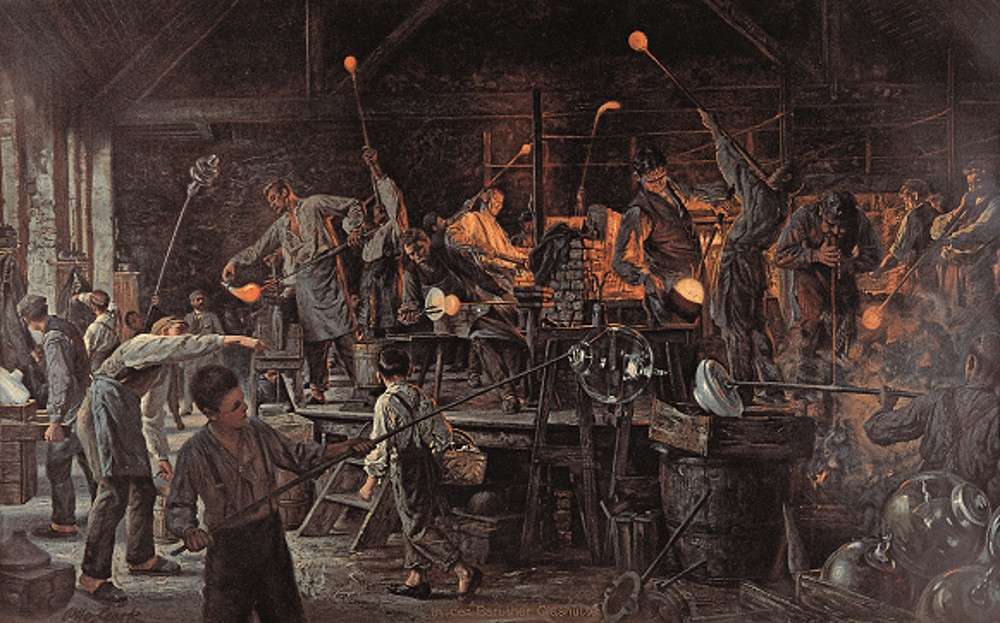

The year 1822 saw a turnaround in the glassworks’ fortunes as market conditions improved. Now under the leadership of Count Friedrich of Solms-Baruth and Ferdinand Adolph Schulz, the glassworks enjoyed great success producing glass chimneys for petroleum lamps and light shades, which were rendered white and opaque by adding ash derived from sheep bones.

By 1844, business was so good that a new factory building was added. Today this is called the “Alte Hütte” – The Old Factory. In this building alone, some 25,000 lamp shades were produced each month. By the middle of the 19th century, the Baruth glassworks had become the largest glass manufacturer in Brandenburg. Most of the existing buildings were constructed during these prosperous decades. By 1870 the village boasted 460 inhabitants, of which 219 were employed in the glassworks. Others were employed in the forestry house in the eastern part of the village. In 1875, four kilometres of track linked the glassworks to the newly completed Berlin to Dresden railway line, which greatly improved the infrastructure. Most of the products were now exported, and many of them were exhibited at different World Fairs.

Fin de Siècle and two World Wars (1880 – 1945)

Increased competition from businesses in Lusatia led to a downturn in profits during the 1880s. The railway connection made it possible to upgrade the furnace to coal power. Bottle making became an important business though lamp shades continued to be the main focus of production. Glass cutting and ornamental work had hitherto been performed with pedal operated machines in Glashütte and nearby Friedrichshof. A steam powered cutting machine was built in 1894, meaning all such work could be carried out locally.

These measures proved to be economically successful and in 1911 the Baruth Glassworks took over the Andreashütte glassworks in Silesia, an area in which the Solms-Baruth dynasty owned a castle and vast estates. Many glassworkers lost their lives on the battlefields of World War I, but production continued throughout, with preserving jars becoming an important product. The glassworks survived the post-war period of hyperinflation and was again refitted in 1927. The Great Depression of the 1930s led to a downturn in business, but again the glassworks managed to survive.

During the Second World War, the National Socialist government declared the glassworks essential to the war effort. With many of the glassworkers conscripted into the army, forced labourers were brought in to compensate for the shortage of labor. They were housed in a small barracks which was located behind the community centre.

While places like Baruth and Halbe were almost totally destroyed in the last days of World War II, the factory colony of Glashütte came through unscathed. A fire in the Siemens gas generator interrupted Glass production only once.

Nationalisation and closure

Production soon resumed after the end of the war. Alfred Kaiser, who had capably run the glassworks for several decades, was removed from his post in 1948 when the communist authorities turned the glassworks into a state owned enterprise. From now on, business decisions were made not in Glashütte but in a central office. In the 1950s it was decided that production of lampshades would cease in Glashütte, to be continued elsewhere. From 1954 Glashütte concentrated on the blowing of large fermentation bottles; since these required no decoration, the grinding department was closed. Foreign demand for these fermentation bottles dwindled in the 1970s, prompting a return in 1976 to the making of lighting glass. During this period, the central authorities failed to invest in modernisation and maintenance. The resulting technical shortcomings and a dilapidated infrastructure led to the permanent closure, in September 1980, of the Baruth glassworks.